With the 2013 Victorian and Federal budgets having been released in the past week, the spotlight is on funding major infrastructure projects across Australia. So how does the government pay for the big infrastructure projects we need to avoid choking on our own growth?

In the case of the state of Victoria, the current favourite way to get finance is via Public Private Partnerships: the government contracts a private consortium to build a piece of infrastructure, then pays them an exorbitant sum over a defined period to operate the facility, before it finally gets handed back to the taxpayer at the end of the term. The best known examples in Melbourne are the CityLink and Eastlink tollways – the desalination plant and the Royal Children’s Hospital are others.

The government says Public Private Partnerships work out cheaper for the taxpayer in the long run, and push the risk onto the private sector – but in reality we end up with socialised losses and privatised profits – greedy bankers making off with the loot when they succeed, and when they fail they sue the government claiming they were misled. In the case of the state of Victoria, we are currently paying a equivalent interest rate of 10 per cent to service PPPs, when the government could borrow money directly for just 3.5 per cent. (see this piece by The Age columnist Kenneth Davidson)

So how the governments fund infrastructure in the old days? When I was looking a newspaper advertising from the early 1980s I found the answer – government bonds. The way they work is simple: an investor loans money to the government, who in return receives a regular stream of interest over the term of the bond, and once the term is up, the investor gets their money back.

So what parts of the government issued bonds?

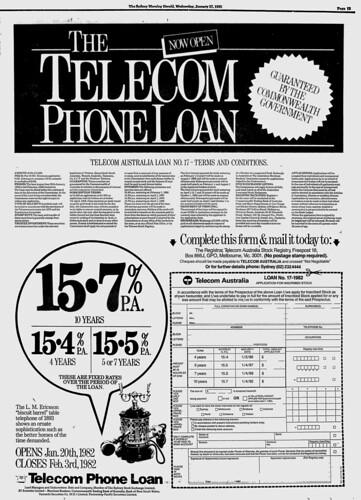

Telecom Australia was one, with their loans being backed by the Commonwealth Government. This was the “The Telecom Phone Loan” No. 17 from 1982 – as for what Telecom Australia intended to do with the money? They probably installed the now clapped out copper wires Malcolm Turnbull and the Coalition wants to reuse for their FTTN version of the National Broadband Network!

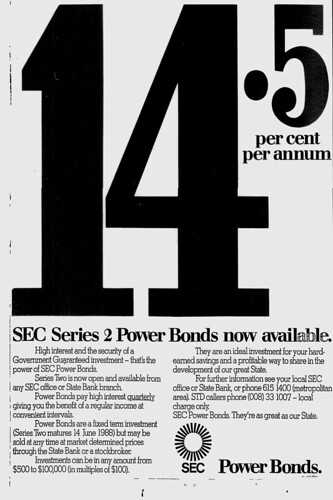

Another government-owned utility to issue bonds was the State Electricity Commission of Victoria. Responsible for the electricity supply to almost all of Victoria (more about the sole exception), back in the early 1980s the SECV was in the middle of building the massive Loy Yang power station and open cut brown coal mine in the Latrobe Valley.

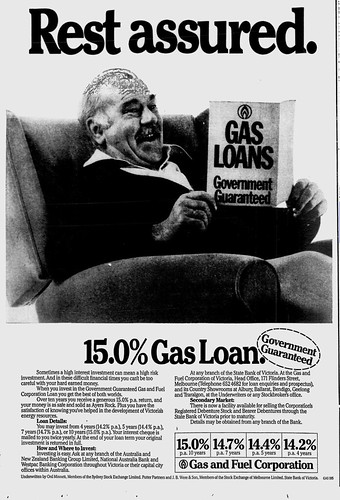

The other big state-owned energy utility was the Gas and Fuel Corporation of Victoria – and they were no stranger to selling government backed debt to the public. With natural gas connected to metropolitan Melbourne by the early 1970s, by the time of their 1983 bond issue they were probably in need of funds to extend their gas pipelines to the smaller regional centres.

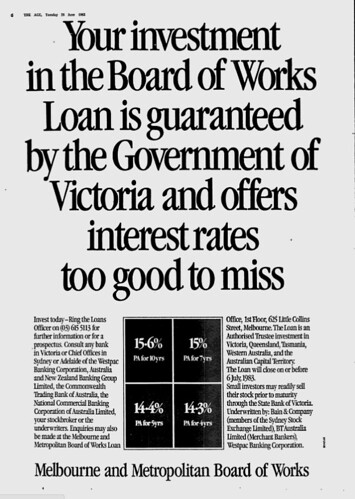

Another pillar of Melbourne before the changes of the Kennett years was the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW). Responsible for water supply and sewers in the city, as well as town planning, management of parkland and other open space, maintenance of metropolitan highways and bridges, and foreshore protection and improvements – the board was another government authority that needed big money to fund capital works.

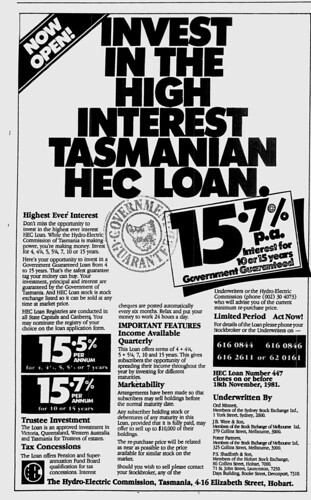

Victoria wasn’t the only state to have state owned agencies issue bonds: over in Tasmania the Hydro-Electric Commission also ran adverts to gain investors. Given the early 1980s timing, the loan money was probably intended for the Franklin River Dam!

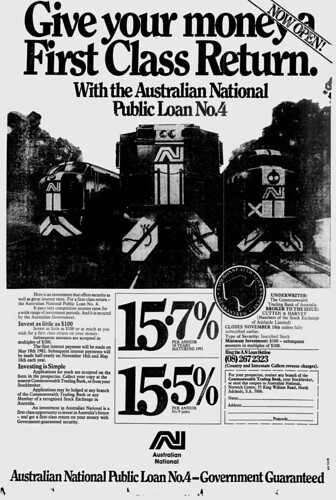

And if you throught public utilities were the only ones to offer loans to the public, the Australian National Railway Commission advertised their Public Loan No. 4 in 1981. Responsible for operating the railways lines inside South Australia, as well as over to Western Australian and the Northern Territory, they probably spent the money on their new fleet of BL class diesel-electric locomotives which were delivered a few years later.

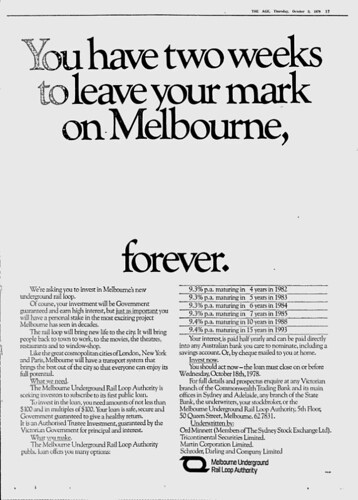

However, I’ve saved the most interesting public loan advertisement for last – that of the Melbourne Underground Rail Loop Authority (MURLA). Established by the government to fund and build what is now known as the City Loop, in 1978-79 it decided to raise $30 million in funds through bond sales to the public, raised further money in the same way in the years to follow.

“Leaving your mark on Melbourne forever” – can you imagine today being able to invest your money in the infrastructure that Melbourne needs, and get paid handsomely for doing so?

Unfortunately it no longer works that way – the proposed Melbourne Metro tunnel is using $3 billion in funding committed by the Gillard government, but it is contingent on $3 billion from an unwilling state government, and another $3 billion via another sketchy Public Private Partnership.

Footnote

If you think interest rates of 10 to 15 per cent are high, you probably didn’t have had a home loan during the 1980s. Back then, high interest rates were the norm.

Further reading

- Need roads and rail? Then borrow and build by The Age economic editor Tim Colebatch

- Hospital PPPs show no signs of good health by Kenneth Davidson, The Age

From the start of the inflationary period, around 1974, through to about 1984, interest rates were very high. You could routinely get 10 to 11 percent on an ordinary bank deposit account. Or building societies, which were very common in those days, but were mostly later taken over or converted into banks and now gone. Meanwhile mortgage loan interest rates were around 13%. Anyone with a job was getting pay rises of about ten percent a year. 48% income tax started around average weekly earnings and 60% cut in at double average weekly earnings, but fringe benefit rorts were almost universal.

This pervasive inflation was disruptive when it started, but once it became routine and entrenched, it seemed quite normal. It was very good for homebuyers, because although the interest rate seemed high, if you borrowed, say, three times your annual wages, then after a couple of years of 10% wage inflation, the ammount you owed seemed much less. And house prices were going up 13% a year. Stamp duty was less in those days. It made much more sense to buy a cheap house and keep “trading up” every few years. That doesn’t make so much sense now.

When my grandfather died in the mid 1970s, it was discovered he had quite a lot invested in government bonds, especially Gas and Fuel loans. The interest rate was very low compared to what was widely available then and no-one will know he chose those as against other more lucrative government loans that were available then. Maybe it was a fixed term matter.

Nevertheless, what a great way for the government to build things by borrowing from its citizens at a fair rate taking into account the security of lending to our government.